Future of Islam in Tunisa

Between Zaytouna and Secular Drift

Tunisia today stands at a crossroads. In the same land where Zaytouna once illuminated North Africa with Islamic scholarship, youth now oscillate between a rebirth of faith and a rejection of religion. On one side, a generation seeks to reclaim authenticity through Qur’an, Sunnah, and tradition. On the other hand, disillusioned youth turn to a cold secular nihilism. This is the paradox of post-revolution Tunisia: the spark of the Arab Spring has ignited both the embers of an Islamic awakening and the ashes of a forgotten identity.

A Legacy of Secular Authoritarianism

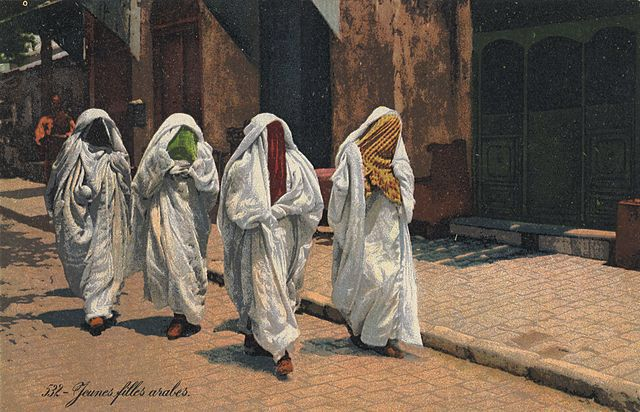

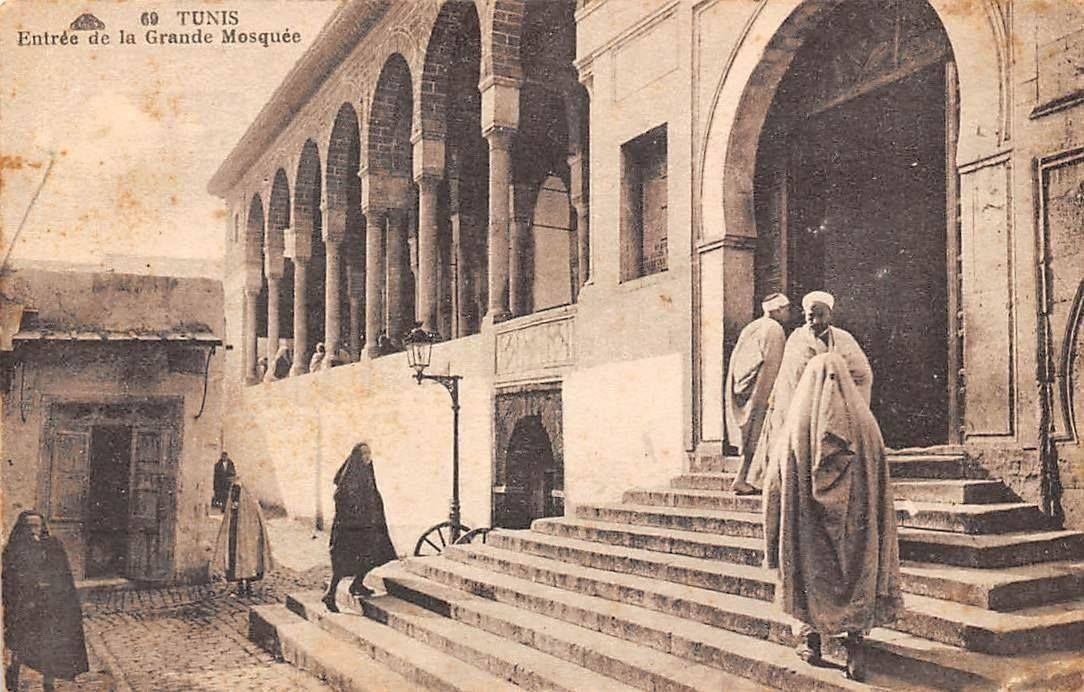

The roots of Tunisia’s religious identity crisis are not recent. Since the French protectorate era that ended in 1956, Islam in Tunisia was gradually displaced from the public sphere. The colonial authorities weakened institutions like Zaytouna, replacing traditional Islamic education with a secular, French-language system designed to mould obedient subjects rather than faithful Muslims. After independence, President Habib Bourguiba carried forward the colonial project under a native face. Bourguiba did not abolish colonial secularism; he simply clothed it in nationalist rhetoric. He shut down madāris, mocked the hijab as "a rag," tried to ban fasting during Ramadan for civil servants, and nationalized the religious endowments (awqāf). Islam was systematically privatized: allowed in homes and hearts, but not in law, schools, or politics. His successor, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, maintained this iron grip on religion. Mosques were monitored, imams were appointed by the state, and anyone speaking of Sharī‘ah was marked a threat, thrown into prisons and tortured there. In this sterile religious climate, many youths grew up with a version of Islam that was either hollow ritualism or state propaganda.

Post-2011: The Return of Religion and the Rise of the Void

The 2011 revolution cracked open the sealed door of public Islam. Salafists, Sufis, Muslim politicians, Qur'an schools, they all returned to a long-silenced stage no matter what aqida they were following. For the first time in decades, Tunisian youth could openly discuss tawḥīd without immediate fear of arrest or torture. Among this opening, a significant number turned toward traditional teachings. These offered a sense of certainty and structure, free from political compromise or philosophical dilution. Yet not all Tunisian youth embraced the Islamic revival. A silent wave of reformism and agnosticism has also risen, particularly among the educated, young urban middle class. Young people, disenchanted with corrupt governments that invoked Islam only as a mask, or traumatized by the social pressures of performative piety, began to question everything, including the divine. Unfortunately, in the privacy of university dorm rooms, a quiet secularization was underway.

Two Paths, One Crisis

On one side, young men started memorizing the Quran and growing their beards for the first time. Sisters begin wearing the hijab or niqāb again, and forming circles of dhikr in university halls. On the other hand, youth openly mock religion, abandon prayer, and repeat slogans of new-age materialism: “Religion is personal” or “Islam is just Arab culture.” Some are even proudly seeking refuge in the West from what they call "religious backwardness." Both groups often come from the same socio-economic background. Both grew up under the same failed state. What differs is how they chose to respond: one seeks structure, the other seeks escape. This is not merely a theological divergence: it is a reflection of a much deeper crisis: the erosion of trust in institutions, in tradition, and in meaning itself.

The Role of the Ulama

In this religious vacuum, traditional ulama have failed to lead. Zaytouna, once the beating heart of Tunisian Islam, has become an empty shell more concerned with administration than daʿwa. Into this silence step YouTube preachers and atheist influencers alike. The space left by their silence has been filled either by YouTube preachers with no firm usūl or by influencers with no spiritual compass. What is needed is a generation of scholars rooted in the tradition yet speaking to the modern condition: addressing doubt with knowledge, not censorship, and speaking to youth with rahma, not rebuke.

“Invite to the way of your Lord with wisdom and good instruction, and argue with them in the best way.” (Qur’an, 16:125)

From Reform to Repression

Yet even as the youth wrestle with faith, doubt, and meaning, the political climate in Tunisia is growing increasingly suffocating. On 25 July 2021, President Kais Saied seized full executive authority, suspending parliament and dismissing the prime minister in what many called a constitutional coup. In the months that followed, he dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council , officially disbanded the parliament, and rewrote the constitution to grant himself sweeping powers: a new charter ratified in a low-turnout referendum on 25 July 2022. Under the banner of “correcting the revolution,” he has criminalized dissent, passed Decree-Law 54 to penalize “false news” with prison sentences, and launched a targeted campaign against political Islam: arresting Ennahda leaders like Rached Ghannouchi and silencing voices affiliated with the Islamic movement. The message is unmistakable: dissent will not be tolerated. The space for political Islam, once cautiously opened after 2011, is shrinking again. With Ennahda leaders imprisoned, Islamic voices muzzled, and criticism increasingly criminalized, a suffocating atmosphere is returning: echoing Ben Ali’s era, but this time cloaked in the legitimacy of “reform.”

The Test of a Generation

In Tunisia, Islam is not dying: it is being fought over. It is being redefined, reclaimed, rejected, and reawakened. The youth are not lost; they are searching. But what they find will depend on who reaches them first: the Netflix screen or the Qur’anic page, the materialist professor or the sabir imam, the false saviours or the voice of the One who says:

“Is He [not best] who guides you in the darkness of the land and the sea?” (Qur’an, 27:63)

Yet faith cannot remain only private, nor morality merely individual. History shows that when Islam is reduced to a matter of personal conscience alone, its ability to shape societies, protect families, and inspire civilizations withers. This is why political Islam understood not as partisan slogans, but as the effort to anchor law, governance, and public life in divine guidance is essential. Without an Islamic framework in society, youth are left vulnerable to nihilism, consumerism, and cultural colonization. If the youth’s longing for meaning finds only apolitical pietism on one side, and militant secularism on the other, the result will be fracture. What is needed is a vision of Islam that governs the heart and the public square, a revival where Zaytouna does not just produce pious individuals, but leaders who can ground Tunisia’s future in justice and moral clarity. The true test of this generation, then, is not only whether young Tunisians will pray, fast, and believe, but whether they will find an Islamic project capable of embodying rahma in society and justice in politics. Only then will the Islamic revival in Tunisia move from scattered sparks to a guiding light.

REFERENCES

Books & Blog Sources:

Amara, T., & McDowall, A. (2021). Tunisian president ousts government in move critics call a coup. Reuters.

Ghannouchi, R. (2013). Public Freedoms in the Islamic State. Tunis: Dar al-Tanmiyya.

Camau, M., & Geisser, V. (2015). The evolution of Tunisian Salafism after the revolution: From la maddhabiyya to Salafi-Malikism. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 47(4), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743815000864.

Belhadj Yahia, E. (2014). Tunisie, questions à mon pays. Paris: Actes Sud.

McCarthy, R. (2014). Re-thinking secularism in post-independence Tunisia. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(5), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.917585.

Web Sources:

Robbins, M. D. (2023). MENA youth lead return to religion. Arab Barometer. https://www.arabbarometer.org/2023/03/mena-youth-lead-return-to-religion/arabbarometer.org.

Al Jazeera Centre for Studies. (2013). The Islamist movement and questions on the 'mehna' (ordeal).